- Press Office

- Ciliates and their bacterial partners

Ciliates and their bacterial partners

Ciliates, just like humans, are colonized by a vast diversity of bacteria. Some ciliates and their bacterial symbionts have become friends for life , as Max Planck researchers and their colleagues demonstrated by comparing a group of these single-celled ciliates and their bacterial partners from the Caribbean and the Mediterranean Seas. They have published their findings in the Proceedings of the Royal Society B. The bacteria provide their ciliate hosts with nutrition by oxidizing sulfur. Surprisingly, they found that this partnership originated once, from a single ciliate ancestor and a single bacterial ancestor, although a whole ocean separates the sampling sites.

Graceful Swimmers

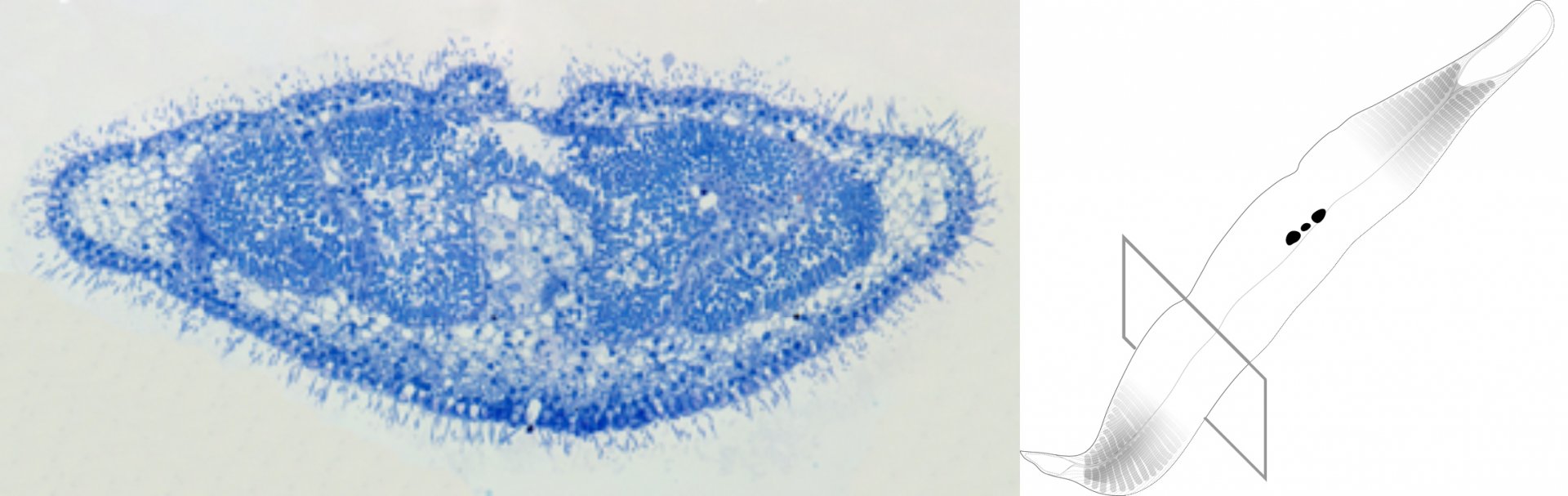

Ciliates are minute, single-celled organisms with several nuclei, and are abundant in freshwater, the oceans and soil. The name “ciliate” comes from 'cilia', tiny hair-like structures, which cover these organisms and are used for movement and to transport food to the mouth-shaped opening. A well-known ciliate is the slipper animalcule Paramecium.

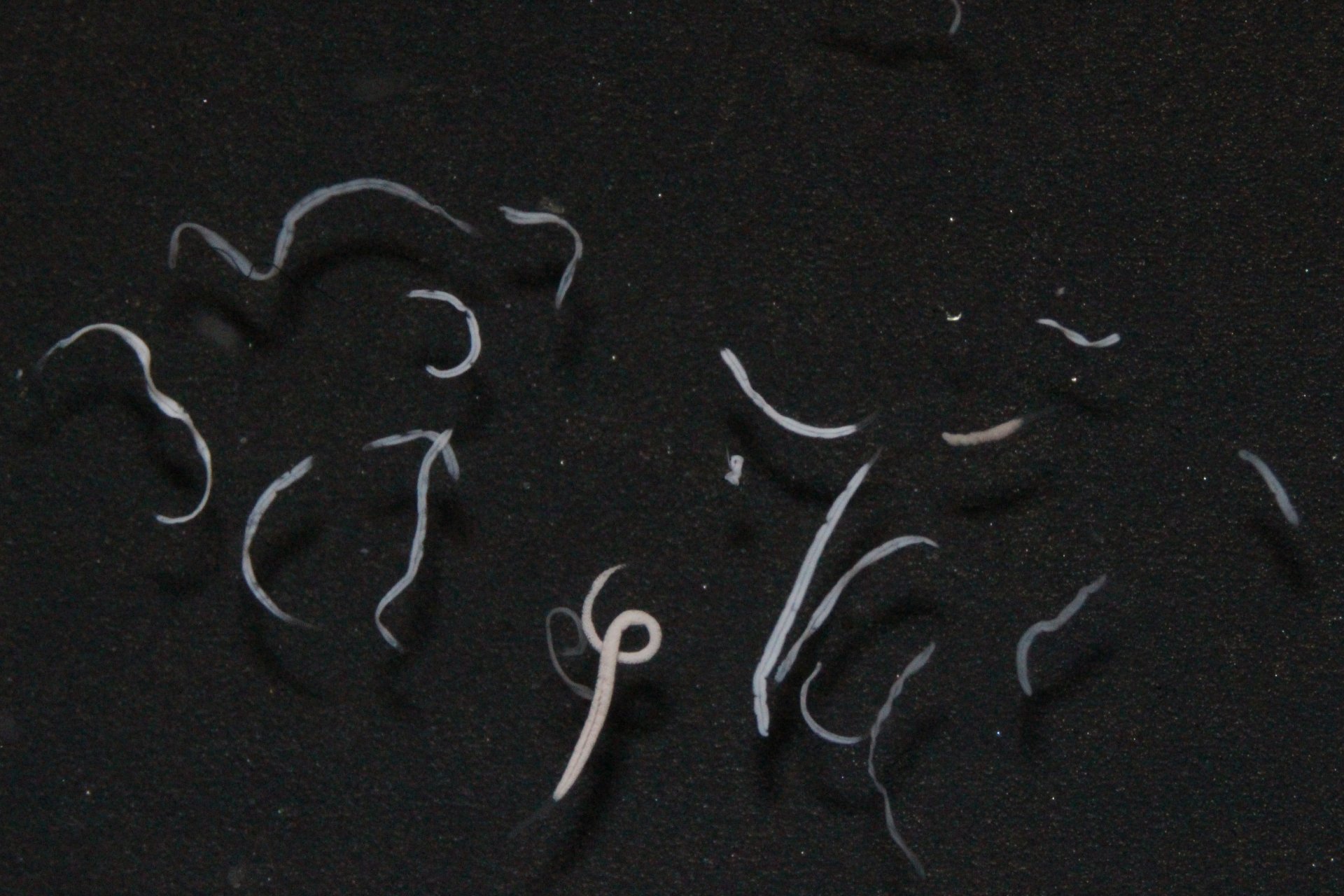

Under the microscope, the elegance and beauty of ciliates becomes obvious. Some species grow to be quite large and are even visible to the naked eye as small dots in a drop of water.

In their study, Brandon Seah from the Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology (MPIMM) and colleagues describe the partnership between ciliates of the genus Kentrophoros, which have lost their mouth opening and the symbiotic sulfur oxidizing bacteria that they depend on. This type of symbiosis is termed mutualism, i.e. both partners depend on each other.

Chemosynthesis and Symbiosis as a Strategy

Many organisms are known which use sulfur-oxidizing bacteria as a source of energy. The first were found by pure chance near the hydrothermal vents in the deep sea in the 1970s. The deep-sea mussel Bathymodiolus and the tubeworm Riftia are two examples. Until now it was not known who the symbionts of Kentrophoros are: are they related to other symbionts, or are they entirely new species of bacteria?

Source: Oliver Jäckle, MPI MM

In their study, the researchers compared Kentrophoros species from the Caribbean and the Mediterranean Seas. Although the overall appearance (phenotype and morphology) varied, DNA sequence analysis showed that the ciliates all originated from a single common ancestor. This was also the case for the bacteria, which all belonged to one group of close relatives from a lineage that is new to science. This means that at some point millions of years ago, the first Kentrophoros and the ancestor of these bacteria formed a partnership that has endured through the years, and their descendants are now found around the world.

“The bacterial symbionts grow only on one side of the ciliate’s body. Some ciliates have special folds in order to increase the area for optimal growth. These ciliates carry their personal vegetable patch that they harvest by phagocytosis,” explains Brandon Seah, PhD student at the MPIMM.

Prof Dr. Nicole Dubilier, Director at the MPIMM says:“ One of the surprising results of our study was that the partnership between the ciliates and their symbionts has been highly stable and specific over a very long evolutionary time period, perhaps tens to hundreds of millions of years. We assumed that because the symbionts sit on the outside of their hosts and could be easily lost when the ciliates move through water or sand, that these symbioses might not be as specific as ones in which the symbionts live inside their hosts. But it turns out that the physical location of partners is not necessarily related to their intimacy.”

The researchers found 17 species of Kentrophoros that are all related to each other, that share the same basic body plan even though each has their own unique features.

Perspectives

The next step on the agenda is genome sequencing of the bacterial symbionts and their hosts. Also, cultivation of the ciliates and their symbionts would open the door for future studies on what contributions each partner in this symbiotic team brings to their relationship.

Original Publication

Seah BKB, Schwaha T, Volland J-M, Huettel B, Dubilier N, Gruber-Vodicka HR. 2017 Specificity in diversity: single origin of a widespread ciliate-bacteria symbiosis. Proc. R. Soc. B 20170764.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2017.0764

Institutes

- Max Planck Institute for Marine Microbiology, Bremen

- Department of Integrative Zoology, and Department of Limnology and Bio-Oceanography, Vienna, Austria

- Max Planck Genome Centre Cologne, Max Planck Institute for Plant Breeding Research, Cologne, Germany

- MARUM, Center for Marine Environmental Sciences, Bremen, Germany

For more information

Ciliates

Ciliates are single-celled organisms with a size of up to several millimeters.

The name Kentrophoros means “spine carrier”, as researchers in the 1920s misinterpreted the bacteria as spines. Kentrophoros are found around the world including the Mediterranean, the Caribbean and the Pacific. They can reproduce asexually.

Ciliates in general have several cell nuclei of two different types. One type is small and carries the genetic information that is exchanged during sexual reproduction. The others control the cell’s functions and its outer appearance via gene expression.

Kentrophoros the Movie –Video clips of live ciliates under the microscope. Source: Brandon Seah

Director

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

3241 |

|

Phone: |

or contact the press office

Head of Press & Communications

MPI for Marine Microbiology

Celsiusstr. 1

D-28359 Bremen

Germany

|

Room: |

1345 |

|

Phone: |